3D Genome Structure Guides Sperm Development

Knowing how the genome folds to turn genes on and off could improve our understanding of fertility and developmental disorders

A single set of genetic instructions produces thousands of structures in our bodies – from nerve cells that branch like gnarled oak trees, to osteoblast cells that sculpt minerals into bone. It begins with the delicate formation of sperm and eggs – which ignite the miraculous unfurling of an entire body from a single cell.

For this to happen, DNA must be precisely folded and coiled into the sperm and egg cells – creating a structure that coordinates thousands of genes, says Satoshi Namekawa, a professor of microbiology and molecular genetics.

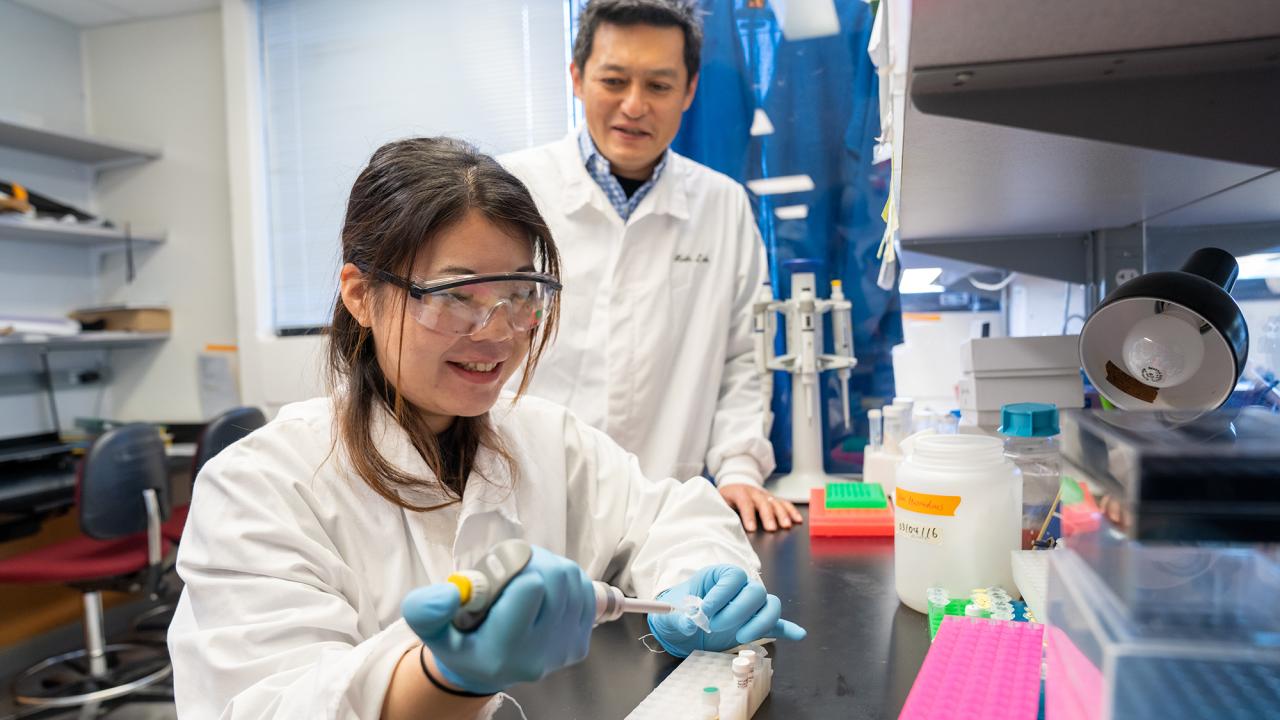

He and his postdoctoral fellow, Yuka Kitamura, have published two landmark papers in the journal Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, which paint a new and stunning picture.

“We are finding the 3D structure of the genome,” says Namekawa. “This is really showing us how the genomic architecture guides development.”

Their work could improve medical care for fertility problems and developmental disorders, which often involve improperly folded DNA.

The linear genome

Scientists have long understood that the DNA molecule – and hence, the genome – is linear, like a string. Some 25,000 genes are scattered along its length, the way stock prices are printed one after another on a ticker tape.

To make different cell types, thousands of genes must turn on and off in different combinations. This is regulated by short segments of DNA, called enhancers, which act as on/off switches for genes.

But as scientists mapped out the positions of these enhancers and the genes that they controlled, they discovered something strange. The on/off switches often sit far from the genes they control, on entirely different parts of the DNA string.

Solving that riddle led to an important discovery in the early 2000s: The genome isn’t just linear. “It is also 3-dimensional,” says Namekawa.

In a living cell, the DNA is folded and looped like a ball of yarn, so that genes and the far-off enhancers that control them are conveniently positioned right next to one another.

To understand how thousands of genes are turned on and off to make different cell types, one has to figure out how the DNA is folded – and which genes and enhancers are paired together.

This insight offered a huge opportunity to Namekawa, who by the late 2010s was trying to understand a critical step in sperm cell development.

The memories of cells

In a mouse or human embryo, the cells that will one day produce sperm or eggs are already earmarked for that future purpose, says Namekawa: “They have a predetermined cellular fate.”

These primordial germ cells (which will later become sperm or eggs) are initially “bipotent” — able to become either sperm or eggs. But while the embryo is still snug in the womb, its bipotent cells commit to one pathway or another — either sperm or eggs — and once they cross that threshold, they cannot go back. “Cells have a sort of memory,” says Namekawa. “But we don’t know how that memory works. We are trying to understand how this male fate is acquired.”

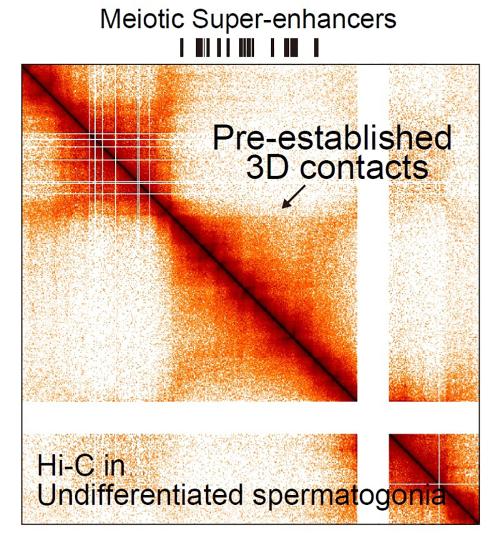

Around 2018, Namekawa and his students began a lengthy effort to discover the 3D genome structure in cells that become sperm. They did this using a technique called “Hi-C.” It isolates thousands of “proximity junctions” where far-flung parts of the genome are paired up next to one another. Using a computer to analyze those paired locations, Namekawa was able to see how the entire string of DNA is looped and folded.

In 2019 he and his colleagues published their first results in the journal Nature Structural & Molecular Biology. They found that in germ cells, the DNA reconfigures so it is looped together only loosely, with just a small number of active genes.

“This 3D genome structure is very different from any other cell types,” says Namekawa. The genomic architecture has reorganized so it is ready to be refolded (and hence, reprogrammed) at the next stage of sperm development, called meiosis, during which haploid cells are produced.

The following year, Namekawa and his colleagues published a second paper. They identified several thousand super-enhancers that turn on genes during meiosis in germ cells.

Bookmarking the genome

In 2021, Yuka Kitamura, a postdoctoral fellow in Namekawa’s lab, began looking more closely at how the 3D genome regulates gene expression.

She found that a protein called SCML2 disconnects the junctions where distant segments of DNA are paired up. This separates thousands of genes from the enhancers that turned them on, allowing the DNA to unfold and loosen.

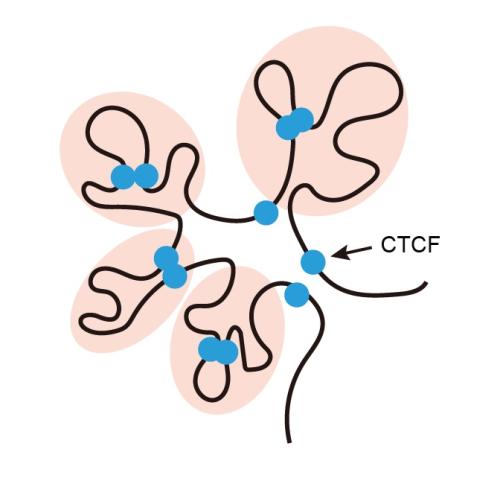

She also found that a second protein called CTCF latches onto a set of super-enhancers — the ones that will become active as the cell enters meiosis. Acting as a connector, CTCF snaps onto other sections of DNA to pair the super-enhances up with the genes that they turn on later during sperm development.

Kitamura, Namekawa, and their collaborators report these insights in a new paper, published March 3 in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology.

“This CTCF-mediated 3D genome structure represents cellular memory,” says Namekawa. This shifting structure turns on a new set of genes – cementing the cell’s future fate, as a sperm cell.

A companion paper, also published in Nature Structural & Molecular Biology, elucidates another important part of this process. It shows that even well before the germ cells enter meiosis, thousands of promoters, stretches of DNA that drive gene expression, are already bookmarked by CTCF and other proteins called transcription factors, which bind to specific locations on the 3D genome. Namekawa and Kitamura published this paper with Bradley Cairns, professor and chair of oncological sciences at the University of Utah School of Medicine.

These discoveries could have important medical implications. Fertility problems often reflect DNA-folding errors in sperm and egg cells. This disrupts gene regulation – rendering the cells unable to produce healthy offspring.

Scientists might one day develop diagnostic tests for genome folding, to illuminate the causes of infertility. Similar discoveries could also help scientists working on stem cell therapies, since coaxing a cell to become a neuron or heart cell requires shifting it from one genetic program to another – each defined by a particular 3D genome structure.

In this way, the genome isn’t simply linear, like a ticker tape. It can also fold and snap into different shapes, like a child’s toy – turning genes on and off to create endless structures.

“We are uncovering the language of cell memory and cell fate,” says Namekawa. “It’s really exciting.”

Additional authors on the two papers include: Kazuki Takahashi (UC Davis, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center); So Maezawa (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Tokyo University of Science in Japan); Yasuhisa Munakata (UC Davis, Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Fukushima Medical University in Japan); Akihiko Sakashita (Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Keio University School of Medicine in Japan); Shawna P. Katz (UC Davis); Noam Kaplan (Israel Institute of Technology); and Chongil Yi (University of Utah School of Medicine). Funding was provided by grants from the National Institutes of Health.

Media Resources

- Douglas Fox is a freelance science writer based in the Bay Area.

- Namekawa Lab

- Cairns Lab

- Attenuated chromatin compartmentalization in meiosis and its maturation in sperm development (Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2019)

- Super-enhancer switching drives a burst in gene expression at the mitosis-to-meiosis transition (Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2020)

- CTCF-mediated 3D chromatin predetermines the gene expression program in the male germline (Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2025)

- ZBTB16/PLZF regulates self-renewal and differentiation of juvenile spermatogonial stem cells through an extensive transcription factor-chromatin poising network (Nature Structural & Molecular Biology 2025)